On this page

Every healthcare organization understands that patient data is sensitive. Electronic health records (EHR) contain information like Social Security numbers, insurance details, medical histories, and billing information. The regulatory environment makes the stakes tangible—HIPAA violations carry penalties ranging from thousands to millions of dollars, plus the reputational damage that follows a publicized breach.

Yet despite the regulations, healthcare networks remain among the most frequently targeted networks of any industry. When security researchers study these breaches, a pattern emerges. Attackers don't need sophisticated zero-day exploits or advanced persistent threat capabilities. They need one compromised credential and a network where inconsistent identity and access management (IAM) policies let them move freely from system to system until they get the data they want.

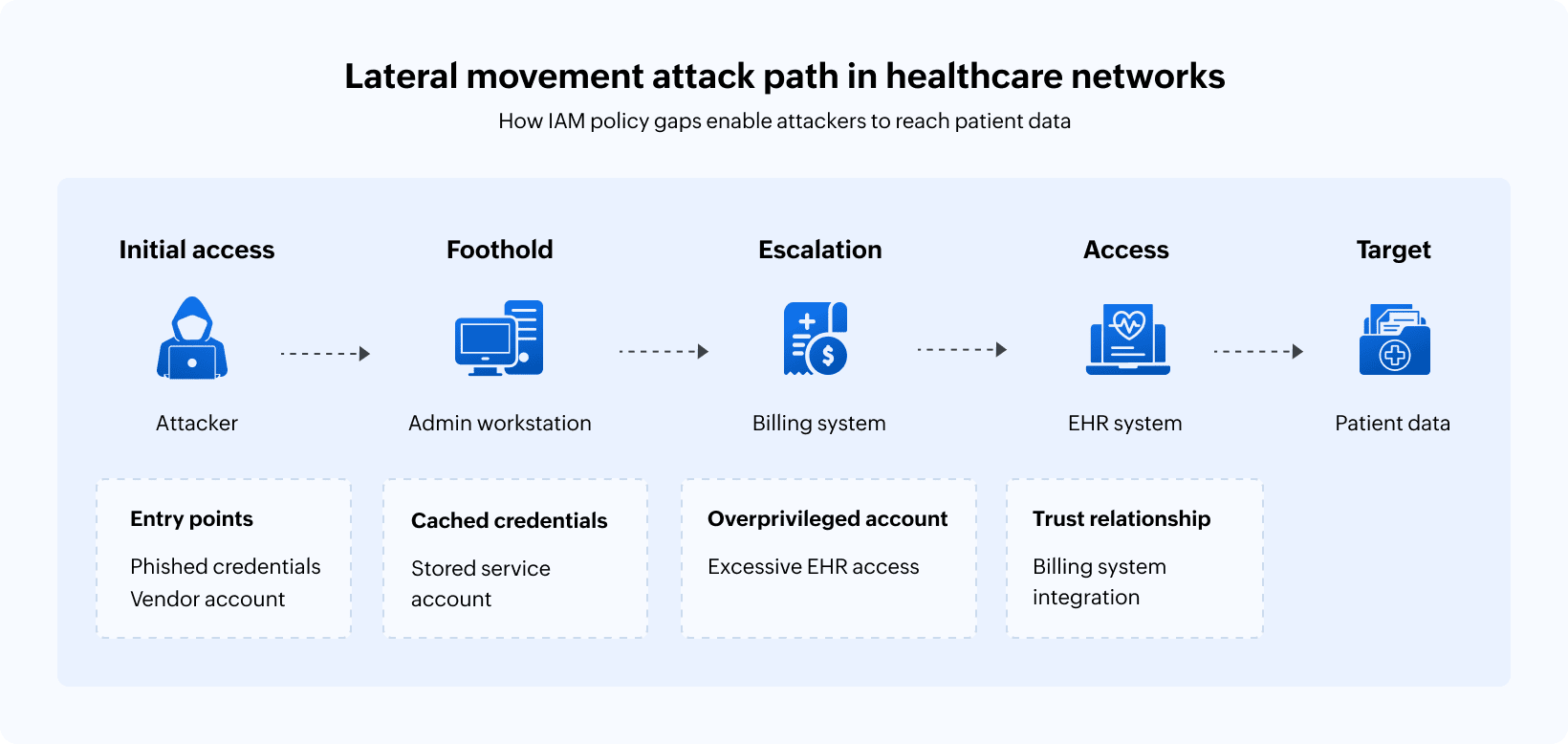

This is lateral movement: An attacker gains initial access through a single point of entry like a phished credential, a compromised vendor account, or an unpatched system, and then navigates through the network by exploiting the gaps between how access should be managed and how it actually is.

The uncomfortable reality is that most healthcare organizations have IAM policies. But they don't have consistency. They miss out on enforcing those policies across every system, department, user account, and access pathway in their environment.

Attackers exploit this inconsistency. And in healthcare, the consequences land directly on patients whose most private information becomes collateral damage.

Why healthcare networks are uniquely vulnerable

Healthcare IT environments weren't designed for security. They evolved organically over decades, accumulating clinical systems, administrative platforms, medical devices, and departmental applications. Each of these brought their own authentication requirements and access models.

A typical hospital network might include an EHR system that handles clinical documentation, a separate patient registration system, a billing platform, laboratory software, and dozens of specialized applications that can help with dietary services, surgery scheduling, and more. Each of these systems may have been installed by different vendors, at different times, with different assumptions about how users should authenticate and what access they should have.

This fragmentation creates identity sprawl. A single nurse might have credentials for eight different systems, each with its own password policy, session timeout rules, and access permissions. The credentials might have been provisioned at different times, possibly by different admins, with varying levels of attention to the principle of least privilege.

When that nurse transfers to a different department or changes roles, some systems might get updated while others won't. When they leave the organization entirely, their primary EHR access gets disabled promptly, but the credentials for that departmental scheduling application might persist indefinitely.

Now multiply this by thousands of employees, including clinical staff, administrative personnel, contractors, vendors with remote access, and affiliated physicians who are not direct employees. The result is an environment where nobody truly knows who has access to what systems.

The anatomy of lateral movement in clinical environments

Lateral movement isn't a single technique. It's a progression through a network using whatever access and credentials are available to reach increasingly valuable targets. In healthcare, this progression often follows a predictable path.

Initial access through the weakest link

Attackers rarely breach healthcare organizations through their most protected systems. Instead, attackers find the entry points where security is weakest. This could be a vendor portal with portal default credentials, an employee who clicked a phishing link, or even a remote access solution configured for convenience rather than security.

The initial foothold might provide just the minimal access, like a workstation on the administrative network or credentials for a low-privilege user account. But that's enough for attackers to begin a probe.

Discovery and credential harvesting

Once inside, attackers observe what's available. They query Active Directory to understand the network structure. They identify which systems and shares they can access. They look for stored credentials that might be found in configuration files, browser password stores, and memory on compromised systems.

Healthcare networks often make this discovery phase easier than it should be. Service accounts with excessive privileges run clinical applications. Shared credentials gets passed among stuff for convenience. Local administrator passwords are reused across workstations because managing unique credentials for hundreds of systems might have seemed impractical during the initial deployment. Each of these discovered credentials becomes a new avenue for lateral movement.

Exploitation of trust relationships

Clinical workflows require systems to communicate. The EHR queries the laboratory system for results. The pharmacy system checks the EHR for medication orders. Radiology receives studies from imaging equipment distributed throughout the facility.

These integrations create trust relationships, and trust relationships create lateral movement opportunities. If the service account that connects the pharmacy system to the EHR has excessive permissions, compromising the pharmacy system provides a pathway to EHR data. If the credentials for the lab interface are stored in plaintext because the legacy system doesn't support modern authentication, those credentials become stepping stones.

Healthcare organizations often discover these trust relationships only during incident investigation, when they're tracing how an attacker moved from a seemingly isolated system to the crown jewels of patient data.

Reaching the target

The ultimate target in most healthcare breaches is patient data. This can be medical records for selling on dark web marketplaces, identity information useful for insurance fraud, or data that can be ransomed back to the organization that can't operate without it.

But lateral movements doesn't always aim directly at the EHR databases. Attackers might target backup systems where patient data is stored with less protection than production systems or compromise administrative systems that have database access for reporting purposes. They're also experts at finding patient data in unexpected locations like spreadsheets on file shares, exports created for analytics projects, or copies maintained by departments for operational convenience.

The path from initial access to patient data might cross a dozen systems. Each step exploits an inconsistency in how access is managed in the healthcare network. Permissions that should have been revoked, service accounts that have unnecessary privileges, and systems that don't enforce the same authentication standards as the rest of the environment are all examples of these inconsistencies.

Where IAM policies break down

Healthcare organizations don't lack IAM policies. They lack consistent implementation of those policies across environments that evolved faster than governance could keep pace.

The policy-practice gap in access provisioning

Written policies typically specify that access should be granted based on job responsibilities, following the principle of least privilege. That is, new employees should receive only the system access necessary for their specific role.

In practice, access provisioning often follows templates. For example, when someone joins the nursing staff, they receive the same access as other nurses in their department. Those templates accumulate permissions over time. A nurse might have requested access to an additional system three years ago for a specific project and that access becomes part of the template. Another nurse needed reporting capabilities that required elevated database permissions and those got added to the template, too.

Today's new hires will receive access profiles that represent the accumulated permissions of every exception granted over years, regardless of whether those permissions are relevant to their actual responsibilities.

Inconsistent deprovisioning across systems

Terminating access should be straightforward: an employee leaves, and access gets revoked. But in environments with dozens of systems and no unified identity management, deprovisioning becomes a checklist exercise, and checklist items get missed.

Deprovisioning the primary systems is obvious: disable the Active Directory account, revoke EHR access, and terminate VPN credentials. But what about the credentials for that vendor-managed imaging system that has its own user database? The departmental application that the IT team doesn't even know exists because a clinical department implemented it independently? The service account that was created under a specific employee's name for an integration project and never transitioned to a proper service identity?

Former employees with persistent access represent a lateral movement goldmine. Their credentials still work, but nobody is using them legitimately, which means there's nobody to receive a "new login" pop-up and no behavioral baseline to trigger alerts. Attackers who obtain these orphaned credentials can operate with reduced risk of detection.

Privileged access without privileged oversight

Healthcare IT operations require administrative access so systems can be configured, applications updated, and integrations maintained. The question isn't whether privileged access should exist, it's how that access is managed.

Inconsistent IAM policies often manifest most clearly in privileged account management. Some systems enforce rigorous controls, like privileged access that require approvals, recorded sessions, and rotating credentials. Other (usually older) systems managed by vendors apply minimal controls because implementing stronger ones would require significant effort or break clinical workflows.

Attackers understand these inconsistencies. They target the systems where privileged access is least protected, knowing that administrative credentials for one system often work on others, and that lateral movement through privileged accounts provides faster pathways to sensitive data.

The vendor and contractor blind spot

Healthcare delivery depends on external parties: Medical device vendors require remote access for maintenance. Software vendors need system access for support and updates. Contractors fill staffing gaps in IT and clinical departments. Affiliated physicians who aren't direct employees need access to patient records for care coordination.

Each external party represents an identity management challenge. Vendor credentials need to be provisioned, monitored, and eventually revoked. But vendors don't appear in the HR system that typically triggers access life cycle events. Contractor engagement ends without the formal termination processes that prompt access reviews. Affiliated physicians maintain access indefinitely because nobody owns the relationship management that would identify when access is no longer needed.

These external identities create lateral movement pathways that internal-focused security controls miss entirely.

Real-world scenarios: When policies fail patients

L et's examine actual breach patterns experienced by three healthcare organizations.

Scenario 1: The compromised vendor and the connected network

A regional health system contracts with a billing services company that requires access to patient financial information. The vendor receives credentials for the billing system and a VPN connection for remote access.

However, the vendor's own environment lacks strong security controls. An attacker compromises the vendor through a phishing attack and obtains the VPN credentials used to connect to the health system's network.

From the vendor's access point, the attacker should only reach the billing system. But network segmentation is incomplete. The billing system sits on the same network segment as several administrative systems. One of those systems has a service account with cached credentials that also work on the patient registration system. The registration system connects to the EHR for demographic updates using a service account with read access to patient records.

It takes just three hops from initial access to patient data. Each hop exploited an inconsistency: incomplete network segmentation, over-privileged service accounts, and credentials cached where they shouldn't have been. The written policies prohibited all of these configurations. The implemented reality permitted them.

Scenario 2: The departed employee and the dormant access

An IT analyst leaves a healthcare organization for a competitor. They depart amicably with proper notice given, and the organization follows standard offboarding procedures. This includes disabling their Active Directory account, revoking badge access, and terminating EHR credentials.

Six months later, the organization detects unusual activity on a legacy clinical system. Investigation reveals that the former employee's credentials for that system were never revoked. The system wasn't on the standard offboarding checklist because it was implemented by a clinical department without IT involvement.

The former employees had sold their credentials. The buyer used them as an entry point, then moved laterally through the network using vulnerabilities shared by the original employee : which systems had weak authentication, which service accounts had excessive permissions, which file shares contained sensitive data in convenient locations.

The breach exposed records for over 100,000 patients. Every patient whose data was accessed could trace the exposure back to a single gap in access deprovisioning—a system that wasn't covered by the IAM policies that should have protected them.

Scenario 3: The clinical device and the network bridge

A medical device vendor installs new patient monitoring equipment throughout a hospital's intensive care units. The devices require network connectivity to transmit patient vitals to clinical dashboards. They also require vendor access for remote maintenance and software updates.

The devices run embedded OSs that can't support modern endpoint protection. They authenticate to the network using shared credentials across all devices. The vendor's remote access solution connects directly to the devices without traversing the hospital's standard VPN infrastructure.

An attacker compromises the vendor's remote access portal. From there, they reach the monitoring devices. The devices sit on a network that was never designed to be isolated. When they were deployed, clinical leadership prioritized rapid implementation over security architecture review.

From the device network, the attacker discovers connections to clinical workstations, which connect to the EHR containing millions of patient records. The monitoring devices, intended to protect patient health, became the attack vector that exposed patient data.

Building IAM consistency across clinical environments

The path from inconsistent IAM policies to consistent identity governance requires addressing fundamental challenges in how healthcare organizations manage access.

Unified identity visibility as the foundation

You can't secure what you can't see. Before healthcare organizations can enforce consistent policies, they need visibility into every identity across every system. This includes employees, contractors, vendors, service accounts, and system integrations.

This visibility must cross traditional IT boundaries, including:

- Clinical systems managed by vendor relationships.

- Departmental applications implemented without IT involvement.

- Medical devices with embedded credentials.

- Legacy systems that predate current identity management platforms.

Building this visibility often reveals uncomfortable truths. You might come across more active accounts than expected employees, service accounts nobody remembers creating, or persistent access for vendors whose contracts ended years ago. However, identifying these vulnerabilities is the starting point for building consistent governance, not reasons to avoid the visibility effort.

Policy enforcement that spans system boundaries

Written policies have value only when they're enforced technically. Consistent IAM requires translating documented access standards into automated controls that apply across the entire environment.

This means implementing access provisioning that derives permissions from defined roles rather than accumulated templates. It also means deprovisioning workflows that trigger across all connected systems when employment status changes and having privileged access controls that apply to every system with administrative capabilities, not just the systems that make enforcement convenient.

Technical enforcement is harder in healthcare than in many industries because clinical systems resist standardization. But the difficulty doesn't eliminate its necessity. The alternative—policies that apply inconsistently based on which systems cooperate with identity governance—is precisely the inconsistency that enables lateral movement in healthcare networks.

Monitoring that detects lateral movement patterns

Consistent IAM policies reduce the opportunities for lateral movement, but they don't eliminate the threat entirely. Sophisticated attackers may find gaps that haven't been closed yet. Legitimate credentials may be stolen through methods that policy consistency can't prevent.

Detection capabilities must identify lateral movement in progress. This can include authentication patterns that show progression across systems, privilege usage that exceeds normal behavior, or access to sensitive resources from accounts that shouldn't reach them.

This detection requires an understanding of what normal looks like for every identity in the environment. For example, a service account that authenticates to the same three systems daily for scheduled tasks looks different from that account suddenly querying Active Directory and accessing file shares. Or, a clinical user who accesses patient records during their shift looks different from that credential being used at 3am from an unfamiliar system.

Behavioral baselines enable anomaly detection that catches lateral movement even when attackers use legitimate credentials obtained through compromise.

Incident response readiness for identity-based attacks

When lateral movement is detected, response speed determines the scope of the breach. Healthcare organizations need incident response capabilities specific to identity-based attacks. This includes the ability to immediately revoke compromised credentials across all systems, trace the path an attacker has taken through access logs, and identify what data may have been accessed during the intrusion.

These capabilities depend on the same visibility and control infrastructure that enables consistent IAM. Organizations that can't see all their identities can't revoke compromised credentials comprehensively. IT teams without centralized access logging can't trace attack paths. Data controllers that don't know where patient data resides can't assess the breach's impact.

Incident response readiness is a side effect of IAM maturity. The investments that enable consistent policies also enable effective response when those policies are tested by real attacks.

The imperative to protect patient data

Healthcare cybersecurity often gets framed as a compliance requirement: Organizations must protect patient data because HIPAA demands it and penalties for violations are severe.

This framing misses the highest stakes.

Patients trust healthcare organizations with information they share with nobody else. Whether it's medical conditions they haven't told their families about, mental health treatment they've kept private from employers, or financial details that could enable identity theft if exposed, the intimacy of this information creates an obligation that transcends regulatory compliance.

When inconsistent IAM policies enable lateral movement that exposes patient data, real people experience the consequences. Identity theft that takes years to untangle. Insurance fraud that affects their coverage. Personal medical information exposed publicly.

Healthcare organizations exist to help patients. Security failures that expose patient data represent a fundamental betrayal of that mission, regardless of whether regulators impose penalties.

The operational case for IAM investment

Beyond patient protection, consistent IAM delivers operational benefits that healthcare organizations need.

Clinical workflows depend on system availability. Ransomware attacks that encrypt systems, often propagated through lateral movement, can shut clinical operations entirely. During ransomware incidents, hospitals have diverted ambulances, postponed surgeries, and returned to paper documentation—operational disruptions that can cost millions per day.

Preventing lateral movement prevents the propagation of ransomware. The investment in consistent IAM that protects patient data also protects operational continuity.

Regulatory compliance becomes easier when IAM is consistent. From demonstrating access controls to producing audit trails—compliance audits become straightforward when identity governance is centralized and comprehensive. While organizations with inconsistent IAM spend audit seasons scrambling to produce evidence from scattered systems, organizations with mature IAM generate compliance documentation as a byproduct of normal operations.

Staff productivity improves when access management is consistent. Clinicians who wait for access provisioning can't see patients, and staff members who can't access systems they need create workarounds that introduce security gaps. Consistent IAM means faster, more reliable access provisioning that gets people the access they need when they need it, without the exceptions and escalations that fragmented identity management requires.

The path forward

Healthcare organizations can't eliminate lateral movement threats by addressing any single gap. The challenge is systemic. Decades of accumulated systems, organic growth without architectural oversight, and clinical priorities that historically outweighed security concerns are all parts of the problem.

Addressing systemic challenges requires systematic approaches. This includes:

- Comprehensive identity discovery across all systems and user types.

- Policy standardization that applies the same controls regardless of system age or ownership.

- Technical enforcement through identity management platforms that span the full environment.

- Continuous monitoring that detects the anomalies indicating lateral movement in progress.

This work is not optional. Attackers have already demonstrated their ability to exploit IAM inconsistencies in healthcare networks, exposing sensitive patient data. The only question is whether your organization addresses these gaps before experiencing a breach or after.

Patient trust, operational continuity, and regulatory compliance all depend on the same foundation: consistent IAM that eliminates the pathways attackers use to move through your network toward patient data. The patients in your care deserve IAM policies that actually deliver comprehensive protection across every system where their data resides.

Related solutions

ManageEngine AD360 provides unified identity life cycle management across Active Directory, Microsoft Entra ID, and enterprise applications. Automate access provisioning and deprovisioning, enforce consistent policies across clinical and administrative systems, and maintain the identity governance that prevents lateral movement through access gaps.

Schedule a personalized demoManageEngine Log360 delivers comprehensive security monitoring with identity-focused threat detection. Track privileged access, detect anomalous authentication patterns, identify lateral movement indicators, and respond to identity-based attacks before patient data is compromised.

Request a personalized demoThis content has been reviewed and approved by Ram Vaidyanathan, IT security and technology consultant at ManageEngine.