Your Windows environment may look secure, but attackers can still escalate privileges by rewriting account identities. RID hijacking is one such hidden threat. Learn how it works and how to defend against it.

What's a RID?

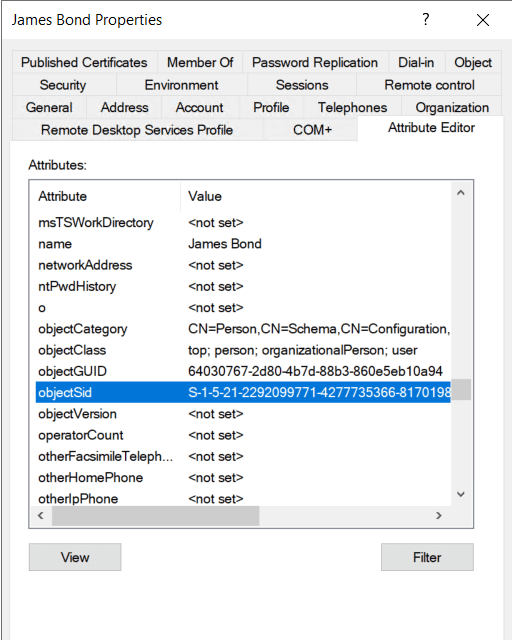

In Windows, every user and group is identified by a security identifier (SID), a unique value that ends with a relative identifier (RID). The RID is the part that distinguishes individual accounts within the same domain, while the rest of the SID identifies the domain itself.

For example, the Domain Admins group has a fixed RID of 512, while regular users are assigned higher RIDs that increase as new accounts are created. When a user logs in, Windows uses the full SID, including the RID, to determine what the user can access.

Did you know?

By default, a domain can support about one billion security principals (e.g., users, groups, computers) due to the RID allocation mechanism.

What's a RID hijacking attack?

A RID hijacking attack happens when an attacker modifies the RID portion of a user account's SID, replacing it with the RID of a privileged built-in account like the local Administrator (RID 500). This makes the system treat the account as if it has admin rights, regardless of its group membership. The change is made locally and requires SYSTEM or administrative access to the machine, so only someone already inside the network can carry out the attack.

Because it uses normal system behavior and does not show up in group lists, RID hijacking is hard to detect.

How does Windows assign RIDs?

Each domain controller has a pool of RIDs it assigns when creating new accounts. The RID is the final portion of the user's SID and represents the account's unique identity in the domain.

Example:

S-1-5-21-2292099771-4277735366-817019834-1105 -> RID

The number 1105 is an automatically assigned RID, typically belonging to a regular user account in a Windows domain.

Common built-in accounts and groups with fixed RIDs

In Active Directory and Windows systems, several built-in accounts and groups are assigned well-known, unchanging RIDs. Some of them are:

| Name | Type | RID | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Administrator | Account | 500 | Default admin account with full system or domain control. |

| Guest | Account | 501 | Default limited-access account, usually disabled by default. |

| Domain Admins | Group | 512 | High-privilege group with full control over the domain. |

| Domain Users | Group | 513 | Default group for all regular domain user accounts. |

| Schema Admins | Group | 518 | Controls the Active Directory schema. |

| Print Operators | Group | 550 | Members can manage printers and print queues on domain controllers. |

Uncovering the tactics of RID hijacking

Attackers typically follow these steps to perform an RID hijacking attack:

1. Gaining access to a system

The attacker first gains local admin or SYSTEM-level access to a Windows machine. This could be a domain-joined workstation or server. The machine must allow the attacker to read and write to the registry.

2. Identifying a regular user account

Next, the attacker locates a standard user account on the machine. This could be a low-privilege domain user or a local account. The goal is to change this account's RID so that the system thinks it belongs to a privileged group.

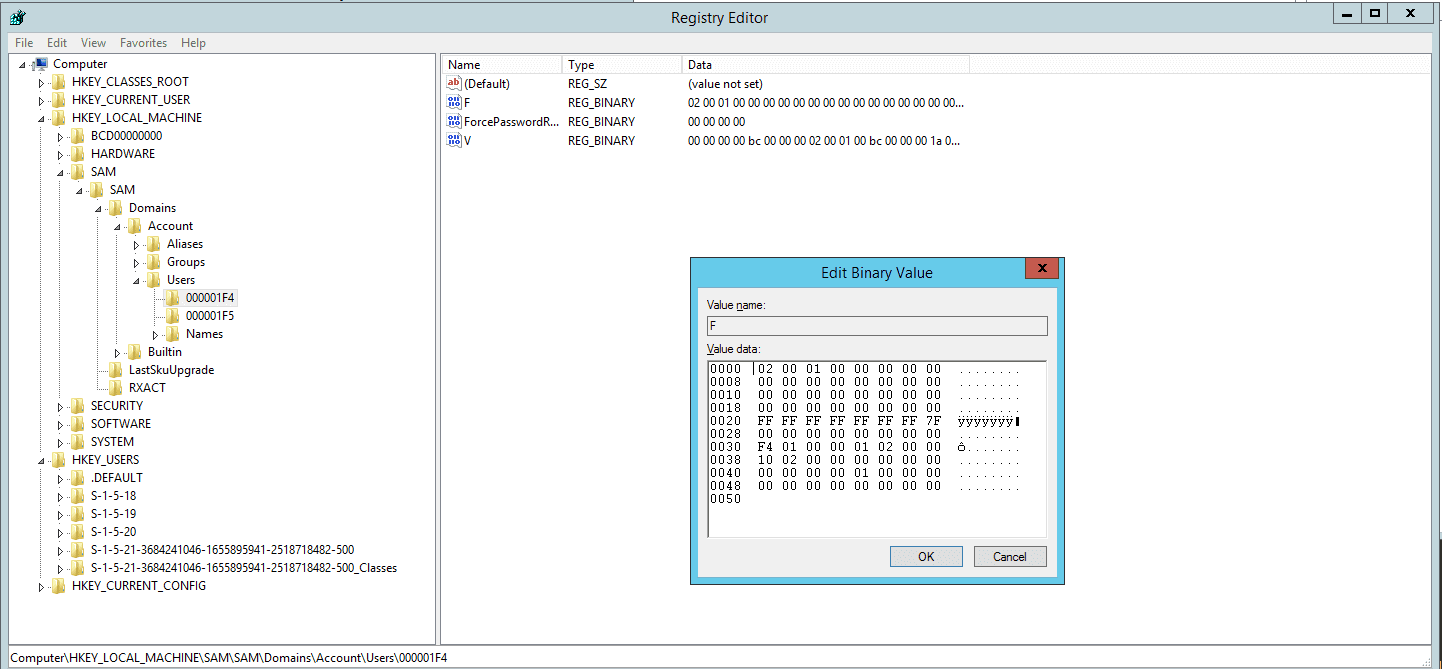

3. Modifying the account's RID in the SAM registry

With SYSTEM-level access, the attacker uses tools like Registry Editor, PowerShell, or specialized post-exploitation frameworks to modify the Security Account Manager (SAM) registry hive. Specifically, they locate the registry key for the target user account, which is typically found at:

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SAM\SAM\Domains\Account\Users\<user>

Within this key, they modify the binary F value, specifically at the RID offset. By replacing the existing RID with that of a privileged account (such as 500 for the built-in Administrator), the system is tricked into treating the user as if they have admin-level access.

4. Gaining elevated access

After logging in, the hijacked account now operates with the privileges of the group associated with the new RID. The system trusts the altered SID, granting full access to sensitive resources, tools, and administrative functions even though the account doesn't officially belong to any admin group.

5. Remaining hidden

This type of hijack attack is hard to spot because group membership doesn't appear changed in tools like ADUC. The user's SID looks normal in domain controllers, and no alerts are raised unless deep SID validation is in place.

How to detect RID hijacking attacks

Detection focuses on identifying suspicious SID mismatches or unexpected privileges associated with normal accounts.

- Accounts showing admin-level access without belonging to admin groups

This is a strong indicator. If a user can perform administrative actions but is not a member of any admin group, it suggests privilege manipulation, possibly via RID hijacking.

- Unusual or duplicate RIDs across multiple accounts

Monitoring for duplicate or unusual RIDs (such as multiple accounts with RID 500) can help detect tampering. However, this requires direct registry inspection or specialized auditing tools, as standard user management tools may not display hidden accounts.

- Unexpected logon events tied to non-admin users performing privileged actions

Reviewing logs for non-admin users executing privileged commands or accessing sensitive resources can help identify compromised accounts. However, this alone does not confirm RID hijacking; it may also indicate other types of privilege escalation or credential misuse.

Key Windows event logs to monitor

- Windows Event ID 4656 (Detect sensitive registry access)

- Windows Event ID 4688 (Detect unusual process execution)

- Windows Event ID 4663 (Detect sensitive registry access)

- Sysmon Event ID 13 (Detect SAM database manipulation attempts)

- Sysmon Event ID 10 (Monitoring SAM registry keys)

How to prevent RID hijacking attacks

- Limit registry access

Ensure that only trusted accounts have access to the SAM registry hive where account data is stored. Regular users and most service accounts should never be allowed to read or modify these sensitive entries. Use Group Policy and security permissions to enforce strict access controls.

- Monitor SID usage patterns

Audit accounts that use well-known RIDs like 500 or 512, especially if they are not normally privileged. This helps catch hijacked accounts that do not show up in group memberships.

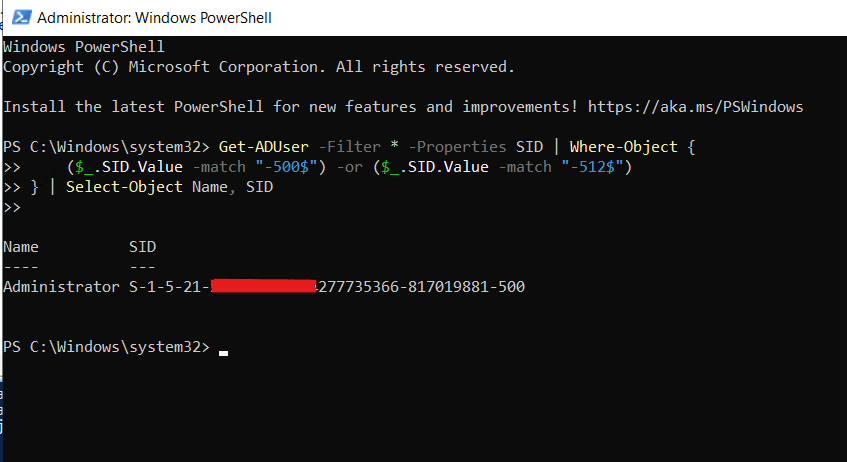

You can run a PowerShell script to list all SIDs and their corresponding accounts:

Get-ADUser -Filter * -Properties SID | Where-Object {

($_.SID.Value -match "-500$") -or ($_.SID.Value -match "-512$")

} | Select-Object Name, SID

This shows all user accounts whose SID ends with -500 or -512.

- Is this user supposed to be using that RID?

- Is it a duplicate of the built-in Administrator?

- Is it not a member of Domain Admins, yet has the same RID as them?

- Restrict local admin access

Stop attackers from gaining admin or SYSTEM-level access in the first place. Remove unused local accounts and enforce least privilege across all endpoints, then harden endpoints through secure configuration and regular patching.

- Use endpoint protection and UBA-driven tools

UBA-driven security solutions can detect abnormal privilege escalations and unauthorized registry access. They help uncover signs of RID tampering, such as sudden access to the SAM hive or unusual activity from accounts that typically lack admin rights.

Now verify:

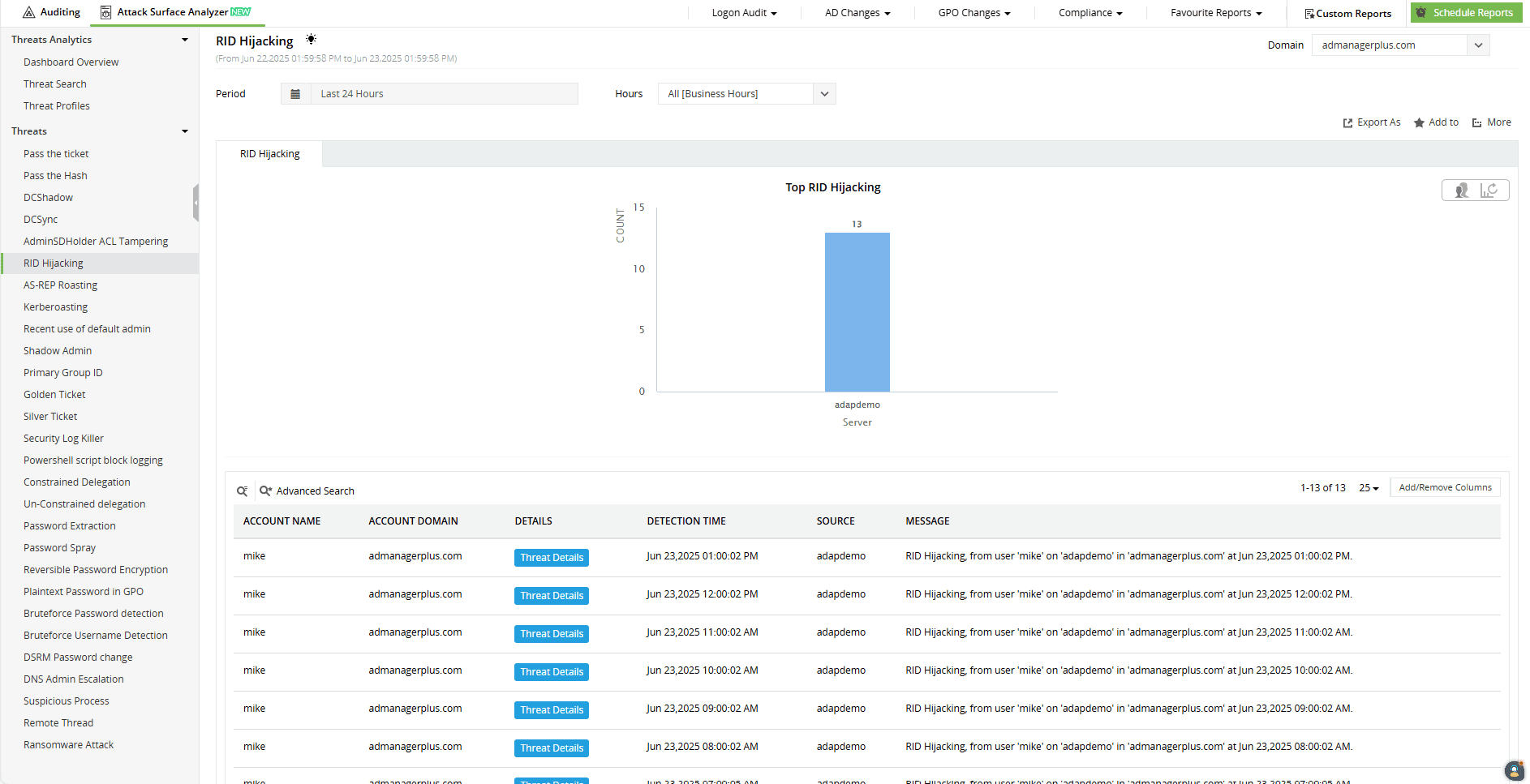

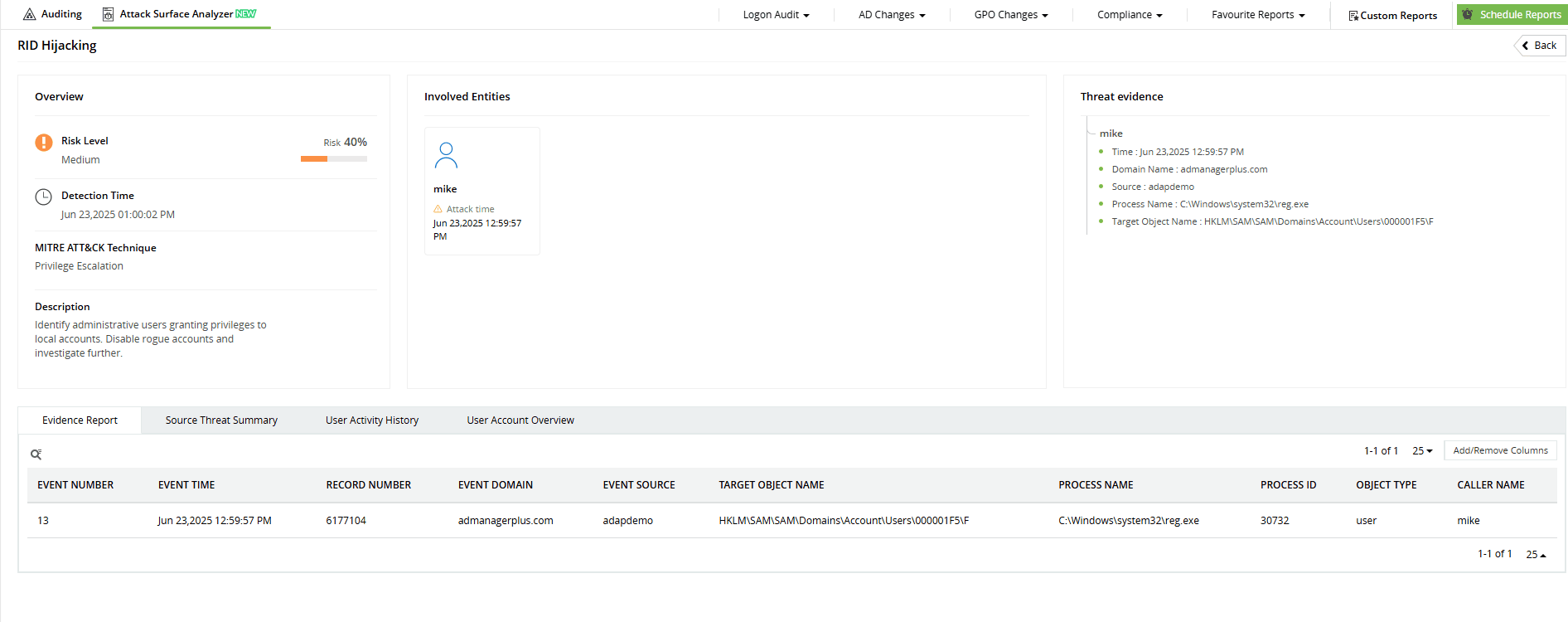

How ADAudit Plus helps detect RID hijacking

ADAudit Plus detects RID hijacking attacks by monitoring changes to a specific registry path within the SAM hive: SAM\SAM\Domains\Account\Users. Its threat detection rules watch for modifications to critical binary values like F, which attackers often tamper with to manipulate RIDs. Combined with alerts for suspicious account activity, ADAudit Plus helps you spot hidden privilege escalation attempts early and take immediate action to protect your environment.

Start protecting your on-premises and cloud AD resources with ADAudit Plus

Detect over 25 different AD attacks and identify potential misconfigurations within your Azure, GCP, and AWS cloud environments with the Attack Surface Analyzer.

See the Attack Surface Analyzer in actionWe're thrilled to be recognized as a Gartner Peer Insights Customers' Choice for Security Incident & Event Management (SIEM) for the fourth year in a row.